For These Families, H.B.C.U.s Aren’t Just an Option. They’re a Tradition

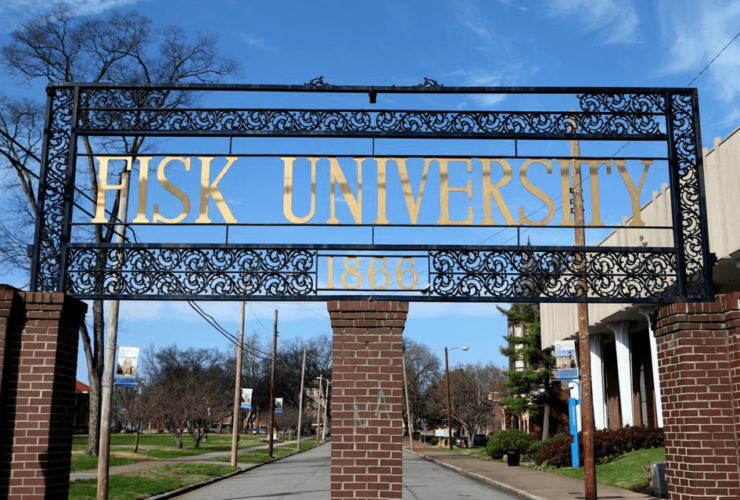

The HBCU designation was created by the US Higher Education Act of 1965 and included institutions established before 1964, with the “principal mission” being the education of Black Americans. The 105 currently operating HBCUs were founded with a common purpose: to educate a population that routinely had been denied even the most rudimentary level of literacy.

From their beginning, HBCUs were intended to be a place of nurturing, a place that recognized that the world was not kind to people of African descent, and a place that recognized the importance of obtaining freedom. Freedom wasn’t just not being enslaved anymore.

Freedom was being able to thrive and survive. HBCUs became known as the places of safety, of comfort, of pride where the journey towards freedom begins, long before the HBCU federal designation. The federal designation was basically a requirement for specific types of federal funding.

HBCUs from the beginning, before and after the abolishment of slavery, during Jim Crow and segregation, throughout the civil rights eras, or as part of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) social justice movement, never wavered from their “principal mission” of using education as a means of obtaining freedom and equality. These institutions continued their “principal mission” even when confronted by laws prohibiting the teaching of slaves to read and write and the physical violence associated with these laws.

There are a range of HBCU origin stories: Some were formed by missionary societies and farmers’ coalitions, others funded by land grants and Quaker philanthropists and oil barons. However, the success of HBCUs was dependent on the students and the parents of those students, who somehow understood that education should be the foundation on which the black family, community and culture be built.

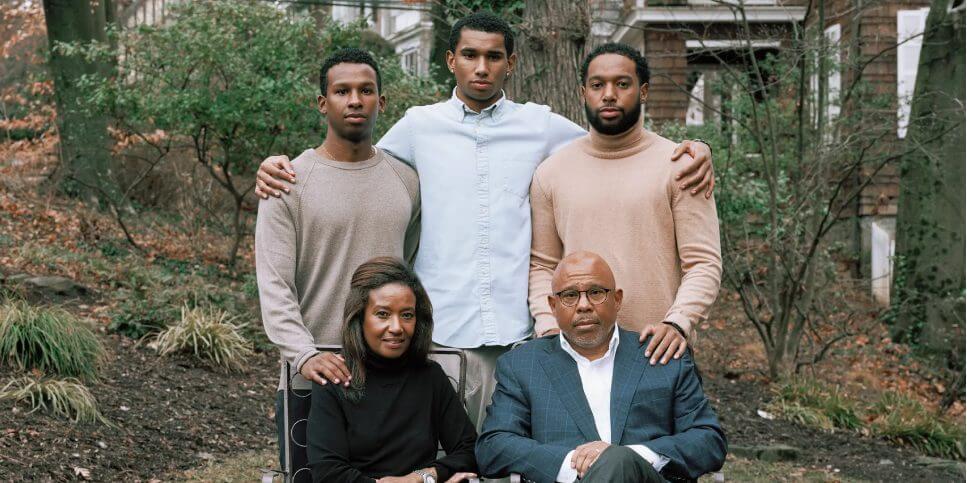

This New York Times article celebrates the tradition of several black families that can point to multiple generations of graduates from the most prestigious of these institutions. It also points out how HBCUs graduates were lifted, anchored, and equipped to set about making changes in the world and bring justice to the black community.

The “principal mission” of the HBCU has not changed and this article recognizes that HBCUs maybe, if not in fact, better at achieving this mission than predominantly white institutions (PWIs). When Black students are in the minority of a student body, they must navigate racial biases and stereotypes. Even if PWIs are not purposefully being negligent, they can often place cultural demands on students that take away bandwidth from really studying, really focusing.

America’s network of Black colleges was founded to provide essential opportunity that were denied people of African descent, and they are a treasured legacy for those families fortunate to be a part of the legacy. However, the “principal mission” of these institutions is not complete.

Accomplishing the “principal mission” was always difficult, “For the South believed an educated Negro to be a dangerous Negro” and constructed legal and illegal means to prevent black education. But to complete the “principal mission” today, HBCUs must compete with PWIs, which are achieving a significant degree of success in attracting and educating black students.

To continue to do this work, HBCUs will need to augment their origin stories by procuring the investment needed to compete by increasing and maintaining student enrollment, attracting faculty/staff, and improving the infrastructure of the institution and the surrounding community.

The HBCU Community Development Corporation is ready to help your HBCU successfully create new origins. If your HBCU needs assistance getting started, contact us now!

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/13/special-series/families-hbcus-graduates-legacy.html